Gold Hedging: A Precious Lesson Learned

Once a key strategy of gold companies, hedging is now nearly non-existent. This, along with a significant commitment to reduce debt, demonstrates the financial health and stability of today’s gold industry.

Perceived dovish comments support small gains for gold and gold stocks

November was an uneventful month for gold. Since August, gold has been consolidating around the US$1,200 per ounce level, and the rout in oil prices that sent WTI crude to a 13-month low of US$50 per barrel had little impact on gold prices. Bullion prices ended at US$1,222.20 per ounce, after trending lower at $1,200 per ounce on November 13. Support late in the month came from the US Federal Reserve's (Fed) dovish comments. Press articles only focused on a small portion of Chairman Jerome Powell’s comments, while the entirety of his speech seemed to suggest that the Fed has not changed its outlook for three interest rate hikes in 2019.

Gold stocks trended sideways with gold in November. The NYSE Arca Gold Miners Index gained 1.2% whereas the MVIS Global Junior Gold Miners Index declined 2.3%; in other words, the juniors and mid-tiers lagged the senior companies.

2019 could be interesting for gold

Last month when the International Monetary Fund (IMF) downgraded its growth forecast for Europe and emerging markets, it suggested conditions have worsened. Germany and Japan experienced negative third quarter GDP growth. As the Fed tightens monetary policies, it is unclear if the US can remain prosperous. Conditions in housing and autos indicate economic weakness has set in. We believe 2019 is shaping up to be an interesting year for gold as we continue to see signs that the US economic expansion is on its final legs.

Once a key strategy, gold hedging now nearly non-existent

The age of hedging for gold companies has long passed. However, we still get questions about hedging from investors and clients. Many remember the scars from hedging strategies that went terribly wrong. Hedging is attractive because gold is almost always in contango, which means the futures and forward prices are almost always higher than the spot price. The forward curve rises as a function of interest rates.

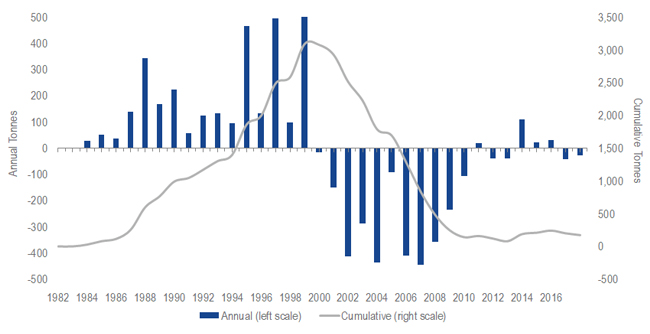

The chart shows the gold mining industry's hedging activity since 1982. From 1987 to 1999, hedging strategies were a key financial component for most companies. Hedging was originally a way to manage risk. It enabled miners to secure credit and protect revenues from falling gold prices. However, hedging became excessive from 1995 to 1999 as companies increasingly used hedging as a way to speculate on the gold price. It was the answer to a secular bear market during the dotcom boom when gold was regarded as an ancient relic and European central banks relentlessly sold their gold reserves. To demonstrate the scale of the super-sized hedging, in 1999, 3,091 tonnes (99.3 million ounces) were hedged, compared to global gold mine production of 2,602 tonnes (83.6 million ounces).

The Golden Age of gold hedging has passed

Net producer hedging 1982 through 2018

Source: Reuters GFMS, World Gold Council, VanEck. Data as of November 2018. For illustrative purposes only.

Lessons learned from the Ashanti crash

As usually happens when anything is taken to excess, a crash soon followed. In September 1999, the price of gold spiked 41%, from US$255 to US$360 per ounce in two weeks, after European central banks agreed to limit their gold sales to an average of 400 tonnes per year for five years. Ashanti Goldfields was a major African producer with operations centered on Ghana. Ashanti, which held 23 million ounces worth of reserves, was producing 1.7 million ounces per year and had plans to expand to 2 million. The company built a gold hedge book totalling 11 million ounces. The book was complex because it used derivative arrangements with 17 counterparties or banks. A significant portion of the book was locked in at prices below US$325, as Ashanti failed to anticipate the hike in gold prices. When the price rose, the value of the book fell to negative US$570 million. This brought margin calls from banks, which amounted to US$270 million. But because the company did not have the liquidity to post margin, it was effectively bankrupt. Although Ashanti ultimately worked out an arrangement with the lenders, shareholder value was decimated in the process. It took several years for Ashanti to gets its finances in order, and in 2004, the company merged with South African major Anglogold.

The Ashanti crash sent shock waves through the gold industry, resulting in the huge decline in hedging from 1999 to 2000. The secular bear market for gold ended in 2001. At the same time the dotcom bust and subsequent decline in the US dollar heralded a secular gold bull market. As the gold price rose, an increasing number of hedge positions that were struck at low gold prices in the 1990s fell underwater. By 2007, gold surpassed US$600 per ounce, and some of the heavily hedged majors had books that were billions of dollars in the red. Fearing a continued rise in gold prices, companies bought back virtually all of their underwater hedges at a great expense to shareholders by 2010.

The next prolonged fall in gold prices came in the cyclical bear market from 2011 to 2015, when the gold price slumped from US$1,920 to US$1,050 per ounce. Through this downturn, hedging was never considered because the industry had learned a painful lesson a few years earlier. The low levels of hedging shown on the chart since 2010 are again aimed at risk control. Many companies have anti-hedging policies, and those that hedge do so with limitations. There are several circumstances where companies sometimes find hedging a small portion of reserves useful:

- Secure near-term cash flow

- Insure revenues for short-life operations with high costs

- Secure financing

Lack of hedging and debt reduction a sign of gold’s financial health and stability

Another area where companies have fundamentally changed their financial approach is with debt. As the gold price peaked between 2010 and 2012, the majors financed many of their new projects and expansions with debt. Low post-crisis rates proved irresistible. As the gold price fell to its 2015 lows, many companies were in danger of violating debt covenants. If the gold price had fallen further, some companies would have been in an Ashanti-like situation, lacking the liquidity to service their financial obligations. This close call has caused companies to pare down debt substantially, and most now target net debt of zero or less. Conservative debt policies are necessary in a business where there is no control over pricing and price swings can be volatile. We believe the gold industry is financially sound and stable now, positioned to possibly generate positive returns for shareholders in the next cycle.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

Published: 10 December 2018