It’s hip to be bonds

We’ve learnt a lot since the 80s and 90s. We’ve moved on from parachute pants, jackets with shoulder pads built in and the mullet. Governments, and how they manage economies, have changed too. In many cases however asset allocation models have not changed. The composition of many investors portfolios are the same as they were in the 80’s and do not reflect a world that has changed. Your investment portfolio should reflect the ‘new world.’

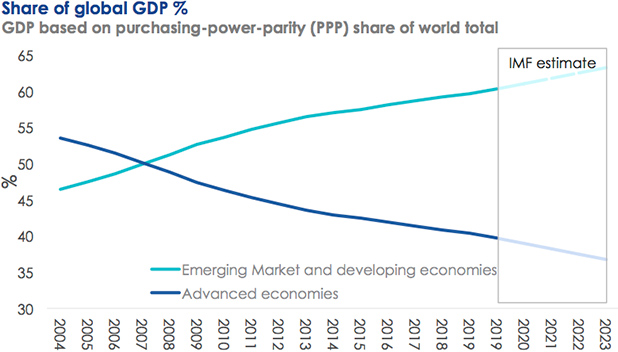

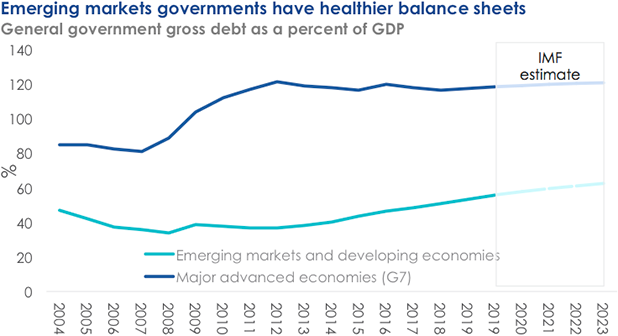

Over the past few decades, emerging markets contribution to global GDP has increased. The IMF expects it will be over 63% by 2023. At the same time emerging market economies have become more structurally sound. Global comparisons show that emerging market economies are less indebted and are as liquid and structurally sound as developed markets.

Source: IMF

Yet many investors still do not have an allocation to emerging markets bonds. Many investor’s portfolios reflect the ‘old world.’

The ‘old world’

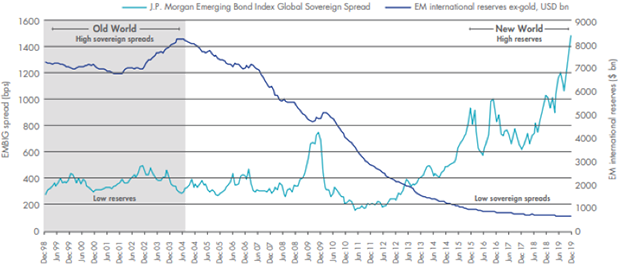

Just two decades ago, emerging markets bonds were risky and volatile due to low reserves, high spending, and the high leverage and vulnerability that this comes with. This led to crises such as the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 and the Russian crisis a year later.

Many emerging markets had a limited ability to repay debt in the 80s and 90s due to low domestic savings. Generally, people in these countries didn’t have faith in their domestic banking system or central bank. They didn’t trust their governments or their policies. The result was these governments were forced to raise funds with US dollars. The only place they could borrow from was the US financial system.

We saw how this played out. When the emerging market’s currency fell, its ability to repay the US dollar debt decreased. Suddenly these emerging markets would find themselves in a downward spiral. Struggling to repay its debt, its currency would weaken even more, making it even harder to repay the US dollar debt. Throughout the process some governments resorted to using their central banks to defend their exchange rate. Those efforts were short-lived because governments ended up worse off, wasting reserves and still ending up with an inevitable default. Put simply, the debt composition of emerging markets countries, being mostly in US dollars, led to many of the emerging markets bond crises in the 80s and 90s.

The way forward: Economic and financial policy reforms

As we know, many emerging markets countries reduced their amount of debt one way, or another. Many defaulted and reduced their debt that way. Others took the harder longer road of spending less, which reduced debt while maintaining credibility. Either way, the response involved governments generating dramatically reduced budget deficits. They implemented structural reforms as well. Some let insolvent banks and companies go bust, which is painful in the short term but healthy in the long term. Governments were forced, often for the first time, to be fully transparent with foreign investors and the International Monetary Fund (which lent them money to get through the crisis, as long as these reform conditions were met).

Many embraced an independent, inflation-targeting central bank that would let the exchange rate float. This structural change could be inflationary, but not if you have anchored inflation expectations with good fiscal policy. Most did and embraced this basic policy response.

The world has changed

Now emerging markets’ current accounts and government budgets are largely in check. Most emerging markets debt is not US dollar denominated, rather it’s mostly local-currency-denominated. In domestic currency, emerging markets no longer need to waste reserves to protect exchange rate levels. They are more resilient as a result. It’s why emerging economies have been growing so much, economically, as well as demographically.

Policy makers, appealing to this ever growing and better educated middle class encourage savings, which helps deepen domestic financial markets and create resilience.

Some of the best managed economies are in emerging markets and they have been able to better withstand shocks to the global economy.

The proof is in the pudding

Evidence of the positive impact of emerging markets economic and financial policy reforms can be witnessed during the global crisis in 2008/2009. Many emerging markets economies came out of the GFC structurally stronger than their developed market counterparts. Several emerging markets governments were able to better implement counter-cyclical fiscal expansion to reignite growth because of their growing foreign exchange reserves, strong budgets and robust balance of payments. In fact, emerging markets were part of the answer to stimulate global growth. China, for example, was able to increase fiscal and monetary stimulus in response to the crisis. In the old days, they would have had to do the exact opposite, bunkering down and tightening, to then suffer a much worse crisis.

Some emerging markets countries didn't even go through recession during the GFC. While the GFC is one example of this working. We’ve also witnessed emerging market’s economic and financial strength during the ‘taper tantrum’.

In 2013, the Fed signalled that it was going to end the latest phase of its quantitative easing. While then Fed chairman, Ben Bernanke did not announce an interest rate hike, the market reacted like he did and became concerned about countries with large current account deficits: Turkey, South Africa, India, Indonesia, and Brazil. With significant reserves they let their currencies weaken and they let their interest rates rise. Even Argentina did that. By weakening their currency and hiking interest rates directly they could address their current account deficit.

In this new world, emerging markets were no longer dependent on US dollar debt so they weren’t afraid of letting their currencies weaken because it wasn’t going to turn into the vicious debt cycle it would have in the ‘old world.’

The new world

Source: Bloomberg. Data as of December 2019. EMBIG spread is the difference between emerging markets hard currency sovereign bonds and US treasuries, and is captured by the J.P. Morgan Emerging Bond Index Global Sovereign Spread.

The “new world” in emerging markets is characterised by higher reserves and lower spreads on bonds. Current accounts and government budgets are largely in check. Policy makers, appealing to an ever growing and better educated middle class encourage savings and pension reforms driving capital investment. Some of the best managed economies are in emerging markets.

It’s little wonder more and more investors are embracing emerging markets bonds, especially when they consider the yields being offered.

This information is issued by VanEck Investments Limited ABN 22 146 596 116 AFSL 416755 as the responsible entity of the VanEck Emerging Income Opportunities Active ETF (Managed Fund) (‘EBND’).

This is general information about financial products and not personal financial advice. It does not take into account any person’s individual objectives, financial situation or needs. Before making an investment decision, you should read the PDS and with the assistance of a financial adviser consider if it is appropriate for your circumstances. The PDS is available at www.vaneck.com.au or by calling 1300 68 38 37.

EBND invests in emerging markets which have specific and heightened risks that are in addition to the typical risks associated with investing in the Australian bond market. The PDS contains details of the key risks.

No member of the VanEck group guarantees the repayment of capital, the payment of income, performance, or any particular rate of return from EBND.

© 2020 Van Eck Associates Corporation. All rights reserved.

Related Insights

Published: 21 February 2020