A playbook for the rest of 2025 and beyond

This year has already delivered more than its fair share of market episodes and once-in-a-decade events.

We had DeepSeek momentarily wiping US$1 trillion off the tech sector, tariff skirmishes playing yo-yo with markets, a darkening US debt cloud and ruptures in geopolitics. Yet the global equity market (as represented by the MSCI ACWI Index) has reached new all-time highs. It begs the question, why didn’t all the turbulence and negative headlines derail the rally? With surprises set to continue, how should portfolios be positioned for the rest of the year, and beyond? Spoiler alert: You’ve probably heard of the approach.

Why didn’t the negative headlines derail the rally?

You may have heard of the “rational inattention” theory by Christopher A. Sims, the winner of the 2011 Nobel Prize, which asserts that human attention is a limited resource. People tend to ignore most incoming information and act only on important signals that are easy to understand and monitor. In investing, this means that only understandable and trackable headlines can shift investor behaviour structurally. Since the turn of the 21st century, global economic growth and rising corporate earnings have been the most consistent trackable trends, guiding the direction of equities.

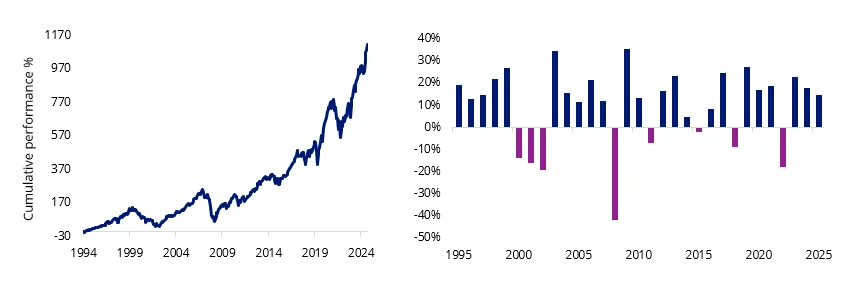

This may explain why, apart from the period after the dot-com bubble bursting, which saw global equities deliver negative returns for three consecutive years, no negative headline has kept the MSCI ACWI Index in decline for more than one year since 1995 (see chart 2).

Chart 1 & 2: The unstoppable equity rally over the past decades. Yearly returns broken down.

Source: VanEck. Bloomberg. MSCI ACWI Net Total Return Index. Performance in USD. Date from 31 December 1994 to 25 August 2025. You can not buy an index. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.

Let’s consider today’s high-stakes items: the global AI race, rising geopolitical tensions, tariffs, the US debt problem and de-dollarisation. On a relative scale, the first two are more trackable and understandable. AI development is reflected in the one-way capex trend by tech giants and earnings reports, while rising geopolitical tensions are evident in expanding defence spending. Investors can price them right here, right now. Both have been positive factors for equities, particularly the tech and defence sectors.

In contrast, tariff terms shift by the day, debt wrangling hides in the thousand-page One Big Beautiful Bill and questions over the US Federal Reserve’s (the Fed) independence, and de-dollarisation moves through complex currency market moves and Fed updates. While investors have not entirely brushed these issues aside, the complexity and volatility they introduce make it too early, and too messy, to fully assess their long-term cost.

How to position for the second half of the year and beyond?

The answer for investors might be simpler than one thought and there’s a good chance you’re already using this approach – a good core-satellite strategy with a healthy dose of rational inattention.

A core-satellite strategy is a portfolio construction approach that divides a portfolio into two components: core and satellite. The 'core' is designed to provide diversified market exposure, balanced across investment styles and company sizes, with the resilience to navigate full market cycles. Core strategies are the 'bread and butter' of a portfolio. On the other hand, the 'satellite' is built to capture specific themes and trends that are believed to add strong upside potential to the portfolio, like the 'cherry on top'.

Research shows that the quality factor, described in academic literature as capturing companies with durable business models and sustainable competitive advantages, has in the past exhibited defensive characteristics. Quality companies (proxied here by the MSCI World ex Australia Quality Net Total Return AUD Index) tend to outperform during economic slowdowns, experiencing smaller declines during market downturns, and recovering more swiftly to previous highs. We think this makes the quality factor a consideration as a ‘core’ component of an international equities core-satellite portfolio.

Chart 3: Quality relative performance versus US Manufacturing activity

Source: VanEck. Bloomberg. 1 December 2000 to 31 July 2025. The ISM Manufacturing PMI Index is often used as an indicator for changes in the economic cycle. A recovery is when economic growth, after the trough of a contraction, starts to head toward growth. An expansion is an environment is when growth is expanding and a faster rate. A slowdown occurs when economic activity slows down after an expansion. A contraction occurs when economic growth is negative, and it is still falling. Quality is the MSCI World ex Australia Quality Net Total Return AUD Index. MSCI ACWI is the MSCI ACWI Index. Performance in AUD. You can not buy an index. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.

From December 2000, as of 25 August 2025, the MSCI World ex Australia Quality Net Total Return AUD Index delivered a cumulative outperformance of ~169% (or 1.3% p.a.) relative to the MSCI ACWI Index. As always, past performance is not indicative of future performance.

Chart 4: Quality relative performance versus US Manufacturing activity

Source: From December 2000 to 25 August 2025, Quality is the MSCI World ex Australia Quality Net Total Return AUD Index and MSCI ACWI is the MSCI ACWI Index. Performance in AUD. You can not buy an index. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.

As a core international equity exposure, quality’s gain may have been able to be enhanced if investors had been able to identify and capitalise on key structural themes. Predicting themes is impossible, but as they emerge, it is possible to take long-to medium-term positions, accepting that you have missed the initial rally. These themes exclude speculative trends that fade quickly and require constant portfolio adjustments; only long-term trends that are trackable and understandable should be considered. As it is also impossible to predict the end of a theme or the emergence of a new theme, a solid core should be able to help cushion rapid market falls.

The following section aims to highlight examples of hypothetical portfolios that had a 70% quality core and 30% exposure to one to two structural trends, across different 5-to-10-year time periods. In each example, the 70% quality core is represented by the QUAL Index, which has been calculated back to 1994. The charts below show the returns of hypothetical portfolios based on a 70/30 asset allocation. These examples are for illustrative purposes only.

1) 1995 to 2000: Dot-Com boom and bust

The 90s were defined by the rapid development of the internet and PC (personal computer) adoption, which led “Dot-Com” to become a buzzword. Growth companies at that time were dominated by tech firms (such as Microsoft and Netscape), and it is hard to miss the tech-led momentum.

Core-Satellite Portfolio: From January 1995 to January 2000, a quality core (using QUAL Index) and a satellite allocation (70%/30%) into developed markets’ growth companies (proxied by MSCI World Growth Index) would have returned 32% p.a., far exceeding the MSCI ACWI’s 22.6% p.a.

Interestingly, even if an investor had held through the Dot-Com bust until January 2003, the portfolio would still have outperformed the MSCI ACWI Index by close to 6.4% p.a., thanks to the resilience of quality stocks cushioning the drawdown.

Chart 5: Hypothetical Quality + Tech-dominated growth companies vs MSCI ACWI Index

Source: VanEck. Bloomberg. Date from 31 January 1995 to 31 January 2003. 70/30 means 70% of the MSCI WORLD ex Australia Quality Net Total Return AUD Index. 30% of the MSCI World Growth Index. Performance in AUD. You can not buy an index. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.

2000 to 2011: The golden era of BRICs and a China-led commodity super-cycle

This era is often referred to as the “golden age” for BRICs (Brazil, Russia, Indian and China). China’s admission to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001 transformed the country into a major engine of global growth, with an average GDP growth of above 10% year on year. This shift triggered a global commodity super-cycle, benefiting emerging economies with heavy exposure to commodities and oil, such as Brazil and Russia. India’s economic growth also accelerated rapidly, driven by an IT services export boom, sweeping market reforms, and a fast-growing, consumption-driven middle class.

Core-Satellite Portfolio: If an investor had a portfolio consisting of 15% of gold miners as represented by the NYSE Arca Gold Miners Index (representing the super commodities cycle with a relative defensive position), 15% emerging markets (EM) as represented by the MSCI Emerging Markets Multi- Factor Select Index, and 70% quality companies as the core sleeve, from December 2001 to December 2011, they could have gained an annualised return of approximately 1.4%, well ahead of MSCI ACWI’s -2.3%. Despite enduring the last years of the dot-com collapse US-led Iraq war, and the global financial crisis, the quality allocation helped cushion drawdowns, while gold miners and EM exposures offered powerful upside from structural tailwinds.

Chart 6: Hypothetical Quality + gold miners + EM portfolio outperformed the MSCI ACWI Index

Source: VanEck. Bloomberg. Date from 31 January 2000 to 31 December 2011. 70/15/15 means 70% of the MSCI ACWI ex Australia Quality Net Total Return AUD Index, 15% of the NYSE Arca Gold Miners Index and 15% of the MSCI Emerging Markets Multi-Factor Select Index. Performance in AUD. You can not buy an index. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.

2) 2011 to 2019: The decade of smartphones and China’s new economy

The post-GFC decade of economic recovery was shaped by two major trends: the rapid adoption of smartphones and the rise of China’s new economy. Apple’s launch of the iPhone in 2007 redefined the smartphone race, while Samsung’s 2010 debut of the Galaxy extended the global reach of the Android system, establishing both companies as unmistakable industry pioneers. Meanwhile, China’s new economy gained momentum, supported by the government’s Strategic Emerging Industries initiative introduced under the 12th Five-Year Plan. Alibaba emerged as a transformative force, revolutionising e-commerce and culminating in its record-breaking IPO in 2014, valued at US$25 billion.

Core-Satellite Portfolio: An investor holding a portfolio composed of 70% quality global companies as the core, 15% in the two leading smartphone companies (equally weighted), and 15% in China’s new economy could have achieved an annual return of ~20% from December 2011 to December 2019, well above the MSCI ACWI’s 14% p.a. The quality core provided steady growth during the bull market, while exposure to China’s new economy and technological transformation captured diversified growth driven by mobile-cloud scale and platform dominance.

Even if the investor had stuck through COVID-19 and the global central bank rate hike cycle, this portfolio would have still outperformed the MSCI ACWI Index by 7% p.a., from 31 December 2011 to 31 December 2022.

Chart 7: Hypothetical Quality + China’s new economy + smartphone transformation vs MSCI ACWI Index

Source: VanEck. Bloomberg. Date from 31 December 2011 to 31 December 2022. 70/15/15 means 70% of the MSCI ACWI ex AUSTRALIA QUALITY Net Total Return AUD Index and 15% of MarketGrader China New Economy Net Return AUD Index and 15% of Apple and Samsung. Performance in AUD. You can not buy an index. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.

3) 2022 till now: the age of AI and the rise of geopolitical tension

Following the global central bank tightening cycle, recent years have been shaped by two major forces: growth led by the breakthrough of generative AI, which transformed business models and boosted efficiency, and escalating geopolitical tensions. The US-China trade war aftermath lingered, while Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 triggered the largest wave of defence spending in Europe since the Cold War. In 2025, Trump’s renewed tariff agenda pushed geopolitical tensions to new highs.

Core-Satellite Portfolio: A portfolio consisting of 70% quality global companies, 15% in global defence companies (proxied by the MarketVector Global Defence Industry (AUD) Index), and 15% in global growth companies (using the MSCI World Growth Index again) led by AI enablers would have compounded at approximately 32%p.a.from December 2022 to July 2025, outperforming the MSCI ACWI’s 23.3% annual return. The quality allocation helped cushion the sharp drawdown during the COVID shock, while exposure to AI-driven efficiency gains and rising defence spending captured powerful structural tailwinds.

Chart 8: Hypothetical Quality + Defence + AI revolution vs MSCI ACWI Index

Source: VanEck. Bloomberg. Date from 31 December 2022 to 31 July 2025. 70/15/15 means 70% of the MSCI World ex Australia Quality Net Total Return AUD Index, 15% the MarketVector Global Defence Industry (AUD) Index and 15% the MSCI World ex Australia Growth Select Index. Performance in AUD. You can not buy an index. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.

Should the current rally run out of steam, as it has in the past, history has shown that having a quality core has supported portfolio resilience amid economic downturns and has helped maintain consistent outperformance compared to the broader global index.

A strong core goes a long way

Outperforming the global equities is an ambition shared by many sophisticated investors. Lessons from the past show that the secret sauce could have been a combination of a strong core, discipline and a healthy dose of rational inattention.

Published: 02 September 2025

Any views expressed are opinions of the author at the time of writing and is not a recommendation to act.

VanEck Investments Limited (ACN 146 596 116 AFSL 416755) (VanEck) is the issuer and responsible entity of all VanEck exchange traded funds (Funds) trading on the ASX. This information is general in nature and not personal advice, it does not take into account any person’s financial objectives, situation or needs. The product disclosure statement (PDS) and the target market determination (TMD) for all Funds are available at vaneck.com.au. You should consider whether or not an investment in any Fund is appropriate for you. Investments in a Fund involve risks associated with financial markets. These risks vary depending on a Fund’s investment objective. Refer to the applicable PDS and TMD for more details on risks. Investment returns and capital are not guaranteed.