Do you have the right Bond?

In February, it was reported that Amazon acquired the controlling interest in the James Bond franchise. Immediately, 007 fans started speculating how Amazon would take the franchise forward. People guessed who the next James Bond would be. Bookies' favourites include Aaron Taylor-Johnson, Theo James and Henry Cavill. There are probably many other potential 007s. While many wonder which actor is right to play Bond, we think it is also worthwhile to consider the right bonds for your portfolio. There is a bond you may have overlooked.

An analysis of Morningstar performance data of all the fixed income ETFs in its Global Broad Category Group category highlights a potential hole in most Australian fixed income portfolios. While we always say, past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance, had you been invested in a broad global bond aggregate ETF over the past three years, your returns would be less than 1% p.a. The best performing Fixed income ETF on Australian exchanges, on the other hand, returned more than 8.50% p.a. (All data 31 May 2025, Morningstar Direct. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance)

And there is little chance, even the savviest investor, would guess where the best-performing fixed income ETF invests…

Emerging markets.

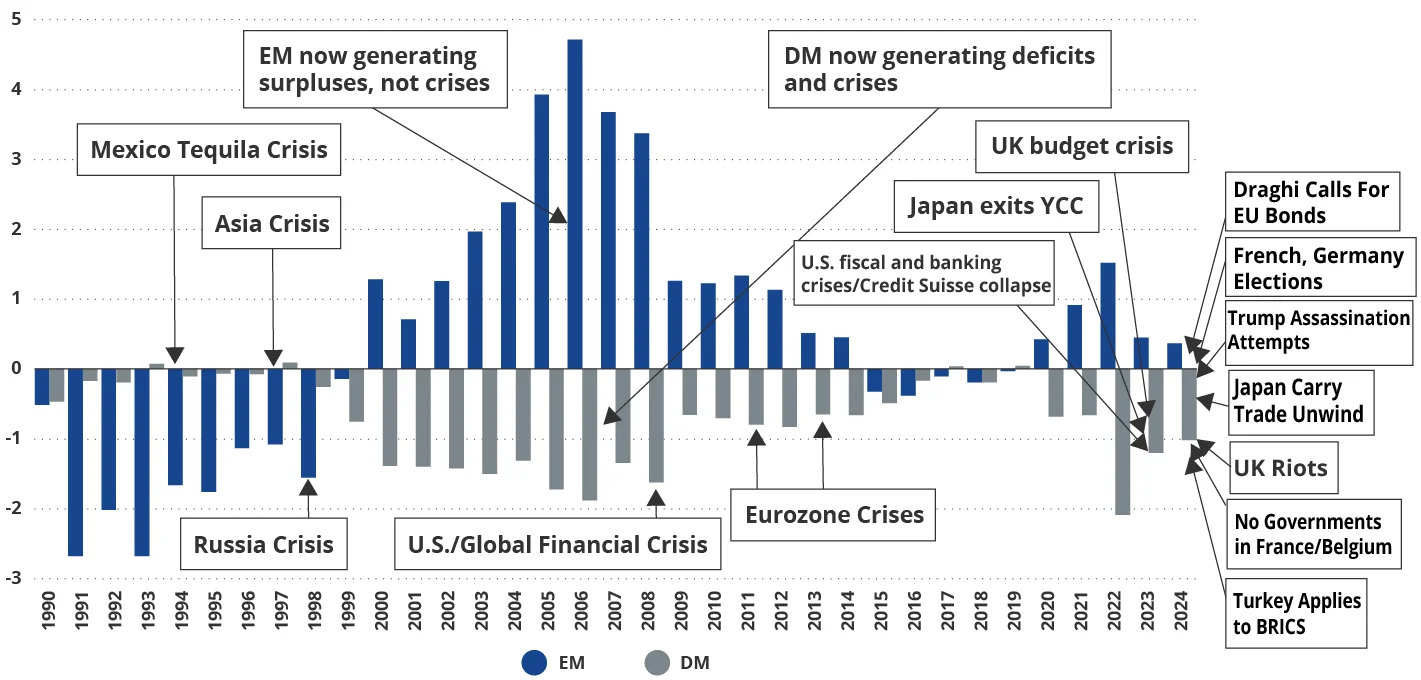

Over the past 25 years, emerging markets governments have gone from being in deficit to running up surpluses, while developed market economies have been accruing deficits. This change has resulted in a shift in the origin of bond crises.

Bond portfolios have yet to reflect this new reality.

We think the story of our emerging markets bonds ETF (EBND) provides an apt narrative that could be considered for investors’ portfolios.

EBND was launched into the eye of the COVID-19 outbreak and subsequent lockdowns that crippled markets in early 2020. In fact, the ETF’s portfolio manager and economist were on the last flight from Australia to the US following an EBND product launch event.

To call the past five years in markets tumultuous, perhaps understates the swings experienced. Developed markets have dealt with Liz Truss’ disastrous UK budget crisis, Japan’s exit from yield curve control, the US regional banking collapse and the collapse of Credit Suisse. Emerging markets have also navigated Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a property crisis in China.

China’s property crisis provides a good example of the growing chasm between emerging markets’ orthodox policy approach and developed markets’ expansionary and experimental approach. Chinese policymakers avoided taking distressed entities onto their balance sheet. This led to collapses in investment-grade corporate bonds. Compare this to the US central bank’s response to the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. A new Banking Term Funding Program (BTFP) was established, and adjustments were made to ease monetary policy.

These different approaches have been a trend since the late 1990s. After the Asia and Russian crises in 1997 and 1998, many emerging markets with the IMF on a “Washington consensus”, which resulted in more independent, inflation-targeting central banks. Exchange rates were floated, and if inflationary, the central bank had to step in with high real rates. If that was recessionary, the recession was allowed. Thailand and Indonesia experienced 50% declines in USD GDP. And insolvent financial and industrial institutions were allowed to fail, that is, they were not bailed out and put on the government’s balance sheet. You can see the persistent surpluses generated due to these policies from about 2000 on, in Chart 1.

Now, compare developed markets’ response to the many crises of the past two and a half decades, and they have been the exact opposite. Recessions were prevented at all costs, insolvent financial institutions were guaranteed, and experimental policies were implemented, resulting in monetary policy enabling fiscal policy. Policy coordination was celebrated.

Chart 1: Almost 30 years of emerging markets exceptionalism

Source: Bloomberg LP, as of December 2024.

Since the GFC, developed market central banks have taken risky assets onto their balance sheet, including high yield ETFs, as was the case with the US. This can stabilise markets, but the moral hazard is that it creates market distortions. The response to inflation, a distortion because of government and central bank stimulation during the COVID crisis, was dealt with differently by emerging markets and developed markets. Most emerging central banks raised rates earlier and more significantly than the late hiking cycle in developed markets. This meant that many emerging markets' central banks, focused solely on inflation, started lowering rates sooner, because inflation was tamed much faster, for the most part. Developed market authorities, who had been forced into more fiscal and monetary experimentation, were managing greater risks.

Australian bond portfolios do not yet reflect this emerging reality.

Bond prices, however, have been reflecting this. Despite launching into one of the most significant market drawdowns in history and experiencing 2022, among the worst calendar years for bond markets globally in over 25 years, EBND outperformed developed market benchmarks. It is worth noting, too, that the asset class, as represented by EBND’s benchmark, has also outperformed developed markets. It is surprising, therefore, that EM bonds are not a part of many investors' portfolios.

Table 1: Trailing returns

Source: Bloomberg, VanEck. Inception date for EBND is 11 February 2020

Benchmark is 50% J.P. Morgan Emerging Market Bond Index Global Diversified Hedged AUD and 50% J.P. Morgan Government Bond Emerging Market Index Global Diversified. Australian Bond Index is Bloomberg Aus Bond Composite 0+ Years. Global Bond Index is Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index Hedged into AUD. The table above shows past performance of the Fund from its inception date. Results are calculated to the last business day of the month and assume immediate reinvestment of distributions. Fund results are net of management fees and costs, but before brokerage fees or bid/ask spreads incurred when investors buy/sell on the ASX. Returns for periods longer than one year are annualised. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of current or future performance which may be lower or higher.

But we don’t think it’s too late for investors to include or increase their allocation to emerging markets bonds for long-term portfolios. That is a key message of a new research paper, which we released last week, analysing the broader global fixed income complex, emerging markets bonds and the fund’s returns since it launched over five years ago.

The research paper is titled, Emerging strength: Why EM Bonds are the future of fixed income.

As the title suggests, we don’t think fixed-income portfolios reflect the new paradigm in global bond markets outlined above and many income-focused investors are missing out. Emerging markets bonds are the future of fixed income.

Because of the idiosyncrasies between the nations included in the emerging markets universe and the nuances between the different types of bonds available, we think an active, unconstrained approach, like the one employed by EBND, is an ideal way for investors to access this important asset class. This discussion is also included in the new research paper.

You can read the new research here.

Past research on EM debt is available here and here.

To learn more about emerging market bonds, register for a webinar with our experts here.

Key risks: An investment in EBND carries risks associated with: ASX trading time differences, emerging markets bonds and currencies, bond markets generally, interest rate movements, issuer default, currency hedging, credit ratings, country and issuer concentration, liquidity, fund manager and fund operations. See the PDS and TMD for details.

Related Insights

Published: 06 June 2025

Any views expressed are opinions of the author at the time of writing and is not a recommendation to act.

VanEck Investments Limited (ACN 146 596 116 AFSL 416755) (VanEck) is the issuer and responsible entity of all VanEck exchange traded funds (Funds) trading on the ASX. This information is general in nature and not personal advice, it does not take into account any person’s financial objectives, situation or needs. The product disclosure statement (PDS) and the target market determination (TMD) for all Funds are available at vaneck.com.au. You should consider whether or not an investment in any Fund is appropriate for you. Investments in a Fund involve risks associated with financial markets. These risks vary depending on a Fund’s investment objective. Refer to the applicable PDS and TMD for more details on risks. Investment returns and capital are not guaranteed.