Property is not out of reach

Australians love property, but each generation has found it harder to get into the market. Find out how A-REITs have made property exposure more accessible.

This blog is adapted from this recording – Banking on Australian Property

Every 15-20 years, a new generation is defined. Each generation is marked by distinct music, fashion, and events that shaped their formative years.

Each generation also has a different relationship with property.

In the post-war era:

- Builders (1925-1945) were busy building the nation, its infrastructure, social institutions, and family homes that we still use today.

- Boomers (1946-1964) were buying with their ears pinned back, capitalising on the economic expansion and suburban growth of the day to secure property.

- Generation X (1965-1980) were leveraging up, borrowing more than their predecessors due to heightened competition and rising prices.

- Millennials (1981-1996) battled to get a foothold into the property market, with house prices strongly outpacing wage growth over the last couple of decades, and heavy reliance on the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’ to support hefty up-front deposits

- Generation Z (1997-2012), meanwhile, are now having to rethink traditional property investing as the silver bullet to prosperity.

One thing all generations have in common is the steep barrier to home ownership, which is becoming much harder and happening much later in life.

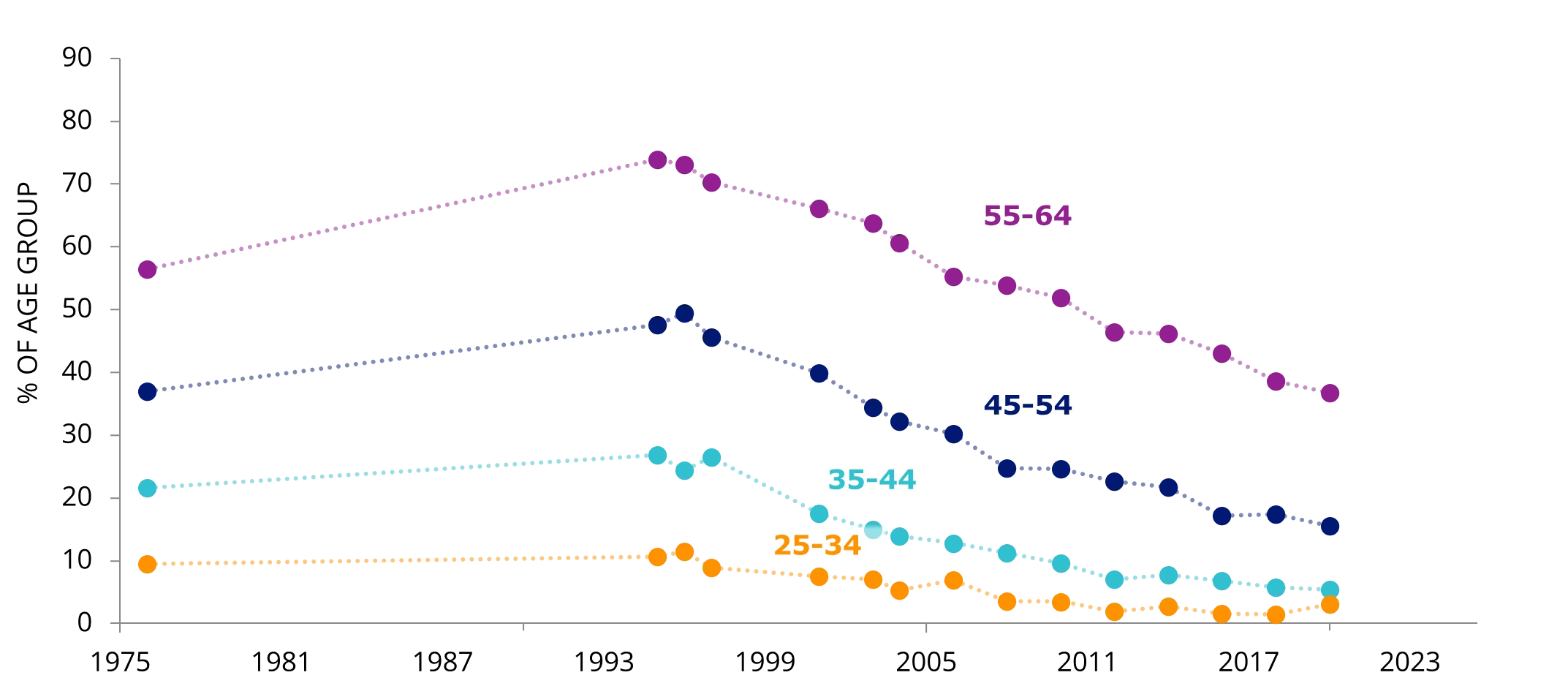

The data tells the story. In 1997, approximately 70% of homeowners aged 55-64 owned their property outright. By the last census, that number had halved.

Chart 1: Home ownership without a mortgage by age group

For younger generations, ownership has become an exception rather than the rule. But while direct ownership may be tougher, Australians’ love affair with property hasn’t faded, it’s just evolving into new forms of investment.

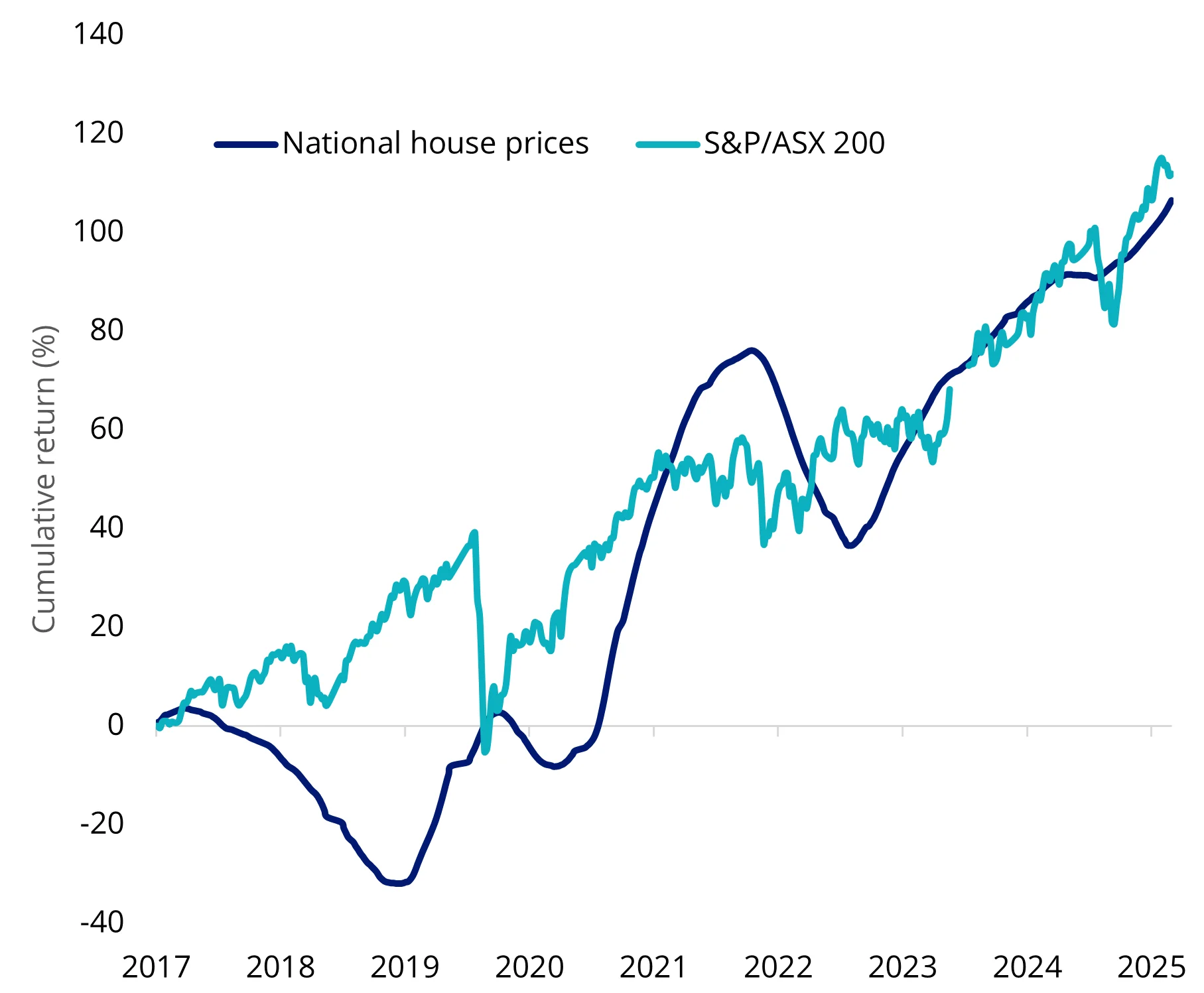

Historically, this love of property has stemmed from the phenomenal capital growth of Australian real estate. The S&P/ASX 200, the barometer of the Australian share market, has returned around 9% per annum over the last 10 years. On aggregate, residential property prices ended roughly in line with the ASX 200 over the same period, although there can be significant variation in performance by dwelling type and location.

Chart 2: Australian residential property roughly matched equity markets over the past 10 years

While property has been a successful investment for some, it has also priced many other Australians out of the market, creating the need for smarter, more accessible ways to gain property exposure.

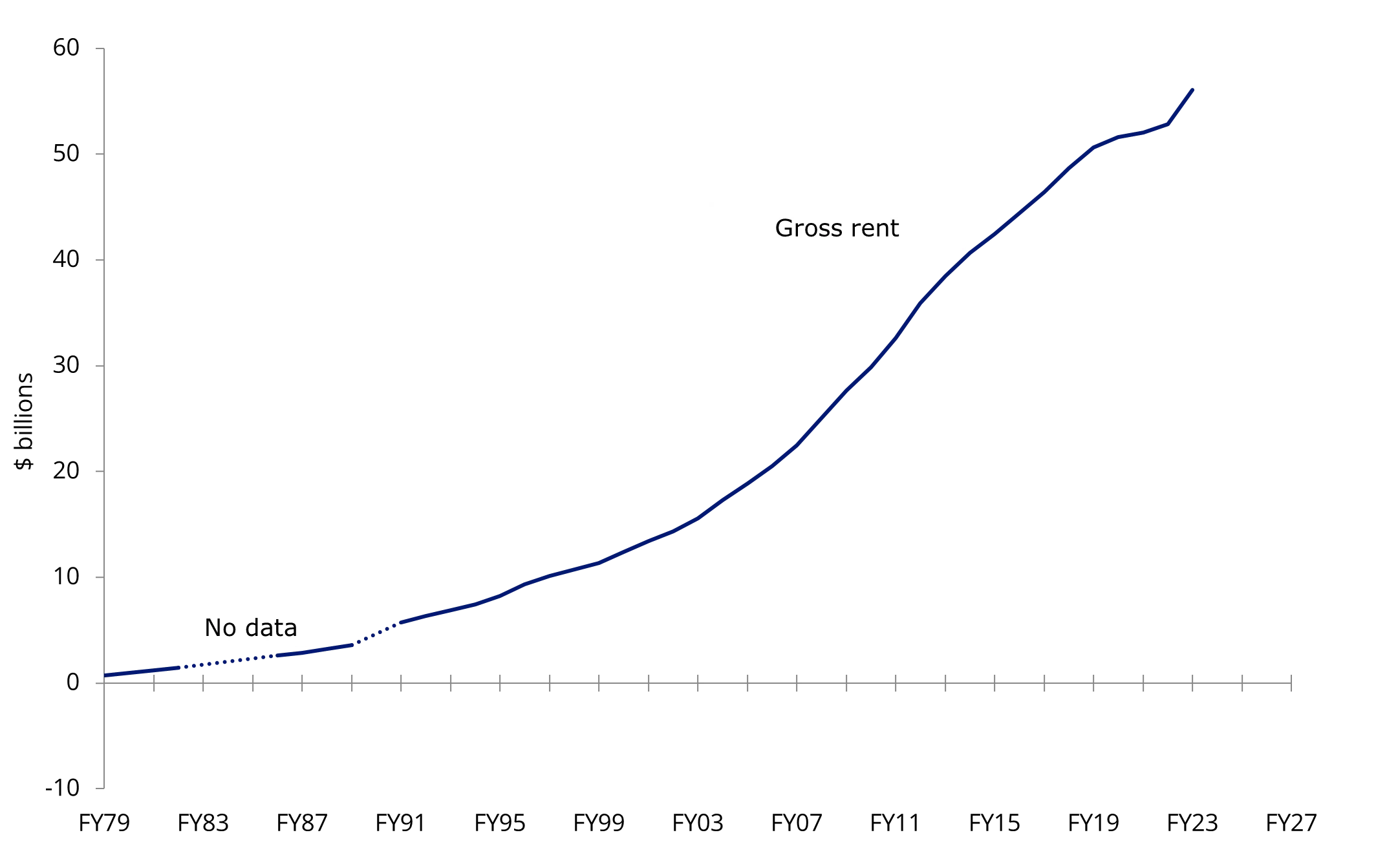

The second reason Aussies love property is income. Rental income has long provided property investors with reliable, steady cash flows. Property income also provides a natural inflation hedge. When inflation pushes the costs of property ownership up, landlords typically respond by raising rents.

Chart 3: Rents have long provided reliable, steady cash flows

Predictable income has made property one of Australia’s favourite asset classes. Yet, for all its appeal, property isn’t perfect.

One of the biggest barriers is the up-front costs. The median dwelling price in Melbourne, which covers both unit and house prices, was just above $800,000 in October 2025, covering a three-bedroom house in Laverton or a much smaller terrace in Fitzroy.

A 20% deposit (the magic number that makes paying expensive lenders mortgage insurance unnecessary) costs $200,000, and there are additional upfront costs to consider such as stamp duty, agency fees, conveyancing, and pest inspections, and the multitude of other fees and costs, which could easily amount to another $50-60,000, and that’s before you get the keys. You’re then up for mortgage repayments, insurance, council rates, strata fees, utilities and maintenance, etc, which effectively eats into the rental income.

The other key drawback of investing in property is its illiquidity. While securities can be sold on the ASX within minutes during market hours, and at a fair price, selling a bricks and mortar investment property can take months of work dealing with real estate agents, open homes and negotiating prices until you find the right buyer.

If the situation is dire, you might even be forced to sell the property for less than it’s worth just to recoup some of the capital.

Thankfully, there are other ways to build a property portfolio that doesn’t involve the stress, debt, and never-ending maintenance bills.

When it comes to property investing, the big end of town aren’t buying up individual houses or apartments; they’re buying entire buildings across residential, retail, offices, storage facilities, and even data centres.

All of these property types provide the growth and income that Australians have long been enamoured with. While commercial property has traditionally been limited to mega-rich property tycoons, Australian Real Estate Investment Trusts, or A-REITs (sometimes referred to as property trusts) have made exposure to these opportunities available to everyday investors.

A-REITs are ASX-listed securities that own, operate or finance income-producing real estate. This income is generated from leasing and selling the underlying property, and this is passed through to investors in the form of dividends.

A-REITs are managed by property investment professionals, who handle the acquisition, management and leasing, and give everyday investors access to real estate portfolios once reserved for institutions.

Scentre Group is an A-REIT that trades on the ASX under the code SCG. It owns and operates 42 Westfields shopping centres across Australia. By holding SCG, you gain exposure to that entire property portfolio.

For those who love houses, A-REITs like Stockland Corporation have a significant proportion of their portfolio dedicated to residential development.

A-REITs deliver what investors love about traditional Australian property: regular income from rents, inflation protection, and the potential for capital growth. They can also add diversification to an investment portfolio thanks to the historically low correlation with traditional asset classes like equities and bonds.

The other key benefit of A-REITs is the ease of access and liquidity. Unlike the exorbitant up-front and ongoing costs and extended settlement process involved with buying and selling property, A-REITs enable investors to gain instant access to a diversified property portfolio with just a few taps or clicks, and for just a few hundred dollars, which can later be sold in an instant and at a fair price.

Naturally, the rewards from investing are commensurate with the risks. A-REITs have many of the same risks as traditional property, and some unique ones too. As with traditional property investment, macroeconomic conditions can impact tenancy rates, while changes in interest rates can influence both property valuations and interest from potential buyers.

A-REITs are also susceptible to market cycles, with a certain level of equity market beta. This means broader movements and sentiment in equity markets can feed through to REITs, given they are listed instruments.

Concentration risk is another consideration. Some A-REITs are focused on specific property sectors or a small number of assets, which presents a higher risk profile than a diversified property portfolio. A-REITs that specialise in office buildings or shopping centres, for example, would have suffered during COVID due to the lockdown and shift to working from home. Taking a diversified approach to REITs investing through ETFs is prudent.

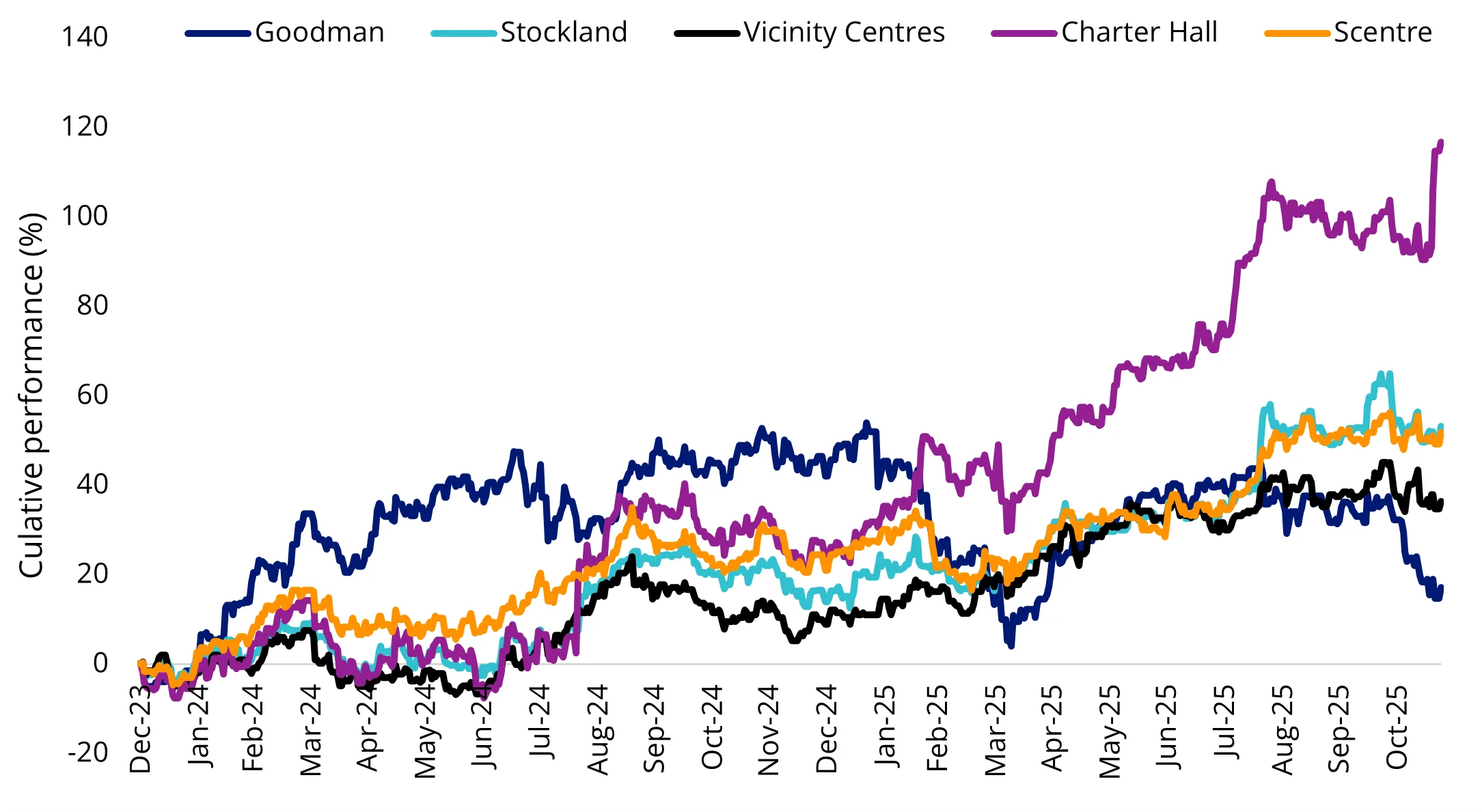

Concentration risk is an issue in Australia’s REITs benchmark, the S&P/ASX 200 A-REIT index (the A-REITs index), as it is dominated by just a handful of large REITs. Goodman Group, which manages industrial property such as warehouses, logistics facilities, office parks and data centres, makes up 38% of the A-REITs index, which means almost 40c of every dollar invested goes to a single A-REIT company.

When Goodman performs well, as it did in 2024, the benchmark gets a lift. But when it underperforms, as it has been in the year to date (-19.12% as at 19 November 2025), it can give a distorted view of the A-REITs sector.

Chart 4: Performance of the biggest A-REITs in 2024 and 2025 YTD

When one company drives an index, investors ride the ups and downs of that one stock, which is why diversification remains a cornerstone of successful, long-term investing. Meaningful diversification is more than just having multiple tickers in your portfolio; it requires balancing exposure across sectors and holdings.

This principle has informed the design of the VanEck Australian Property ETF (MVA), which caps holdings to a maximum of 10%. This approach creates a portfolio that provides a truer reflection of Australia’s commercial property landscape, avoiding overconcentration in the biggest names and providing meaningful exposure to the smaller names so they can contribute to the portfolio’s performance.

MVA is underweight Goodman Group by 28% and overweight Charter Hall by 4% relative to the benchmark. The efficacy of this approach has most recently been demonstrated this year with Charter Hall’s impressive performance this year, effectively usurping Goodman as the new A-REITs hero. You can see this in the chart above.

As one of the first ETFs we listed on the ASX back in 2013, MVA has a proven track record, and has outperformed the A-REITs index since its inception. You can see the performance here – MVA performance.

This blog is adapted from a presentation we game at the November ASX Investor Day. A shortened recording of the presentation is available here – Banking on Australian Property

Key risks

An investment in our Australian Property ETF carries risks associated with: financial markets generally, individual company management, industry sectors, stock and sector concentration, fund operations and tracking an index. See the VanEck Australian Property ETF PDS and TMD for more details.

MVA is likely to be appropriate for a consumer who is seeking capital growth and a regular income distribution, is intending to use the product as a minor or satellite allocation within a portfolio, has an investme

Published: 25 November 2025

Any views expressed are opinions of the author at the time of writing and is not a recommendation to act.

VanEck Investments Limited (ACN 146 596 116 AFSL 416755) (VanEck) is the issuer and responsible entity of all VanEck exchange traded funds (Funds) trading on the ASX. This information is general in nature and not personal advice, it does not take into account any person’s financial objectives, situation or needs. The product disclosure statement (PDS) and the target market determination (TMD) for all Funds are available at vaneck.com.au. You should consider whether or not an investment in any Fund is appropriate for you. Investments in a Fund involve risks associated with financial markets. These risks vary depending on a Fund’s investment objective. Refer to the applicable PDS and TMD for more details on risks. Investment returns and capital are not guaranteed.